All Aboard the RMS Titanic

A new exhibit at Schenectady's Armory Studios NY submerges history buffs in the memory of the fateful day the Ship of Dreams sank to the bottom of the Atlantic.

Stepping through the heavy wooden doors of Armory Studios NY felt like crossing a threshold—leaving one world behind for another. They don’t build places like this anymore. The Armory’s Art Deco bones echo a time of American optimism—less chrome than the Empire State or Chrysler buildings, but unmistakable in its craftsmanship, from the brown-brick archways to its soaring scale.

The RMS Titanic belonged to that same era of ambition. She was built as a monument to progress—to man’s confidence in steel, engineering, and the promises printed in glossy brochures. Her creators imagined themselves beyond the reach of storms, sea gods, and maritime superstition. Many believed she was indeed unsinkable.

It wasn’t long ago that the Titanic dominated pop culture. James Cameron’s blockbuster movie seized the collective imagination—a doomed ocean liner undone by human hubris and an unwavering belief in technology’s supremacy. That arrogance has echoed through history. But before the film, before the documentaries and message-board debates, I remember when the ship simply rested—silent beneath the North Atlantic, lost to time, the weight of her story and the souls aboard still a mystery.

Like millions of others, I watched Cameron’s film more than once. Afterwards came the books—Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember among them—and nights spent poring over survivor accounts the way people now consume social media. It was an early form of doomscrolling, propelled by the need to understand the Whys and Hows of tragedy.

Cameron’s deep-sea fascination placed moviegoers on the ship’s decks in 1997. He guided us through opulent salons, introduced us to both the social elite and the humble travelers below, most of whom shared the same fate. On the surface, the film played as a love story. Beneath it, he offered a meticulous farewell to the waning days of the Gilded Age.

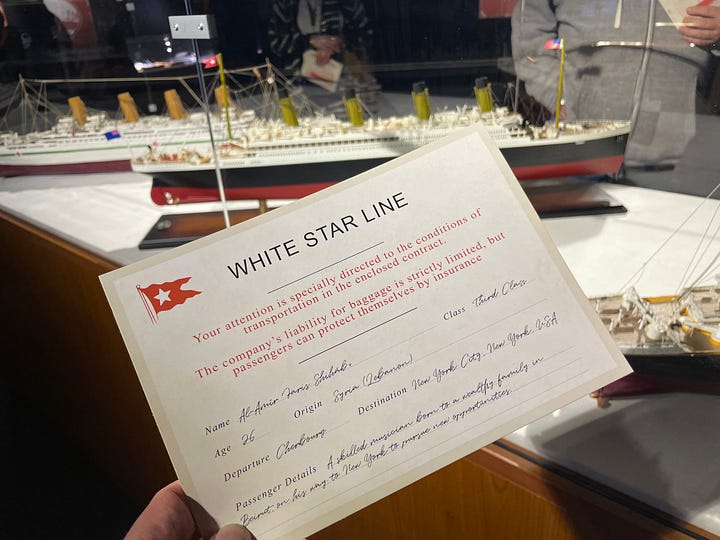

Titanic: An Immersive Voyage – Through the Eyes of the Passengers, a new exhibit at Armory Studios NY, captured that intimacy the moment an usher handed my wife and me our cards. Each carried the name and details of one of the 1,322 passengers: where they were from, how old they were, why they traveled, and in which class. We were each assigned a life. Hers belonged to a woman in first class. Mine belonged to a man in third.

“You’ll learn at the end of the tour whether your passenger survived,” the usher said.

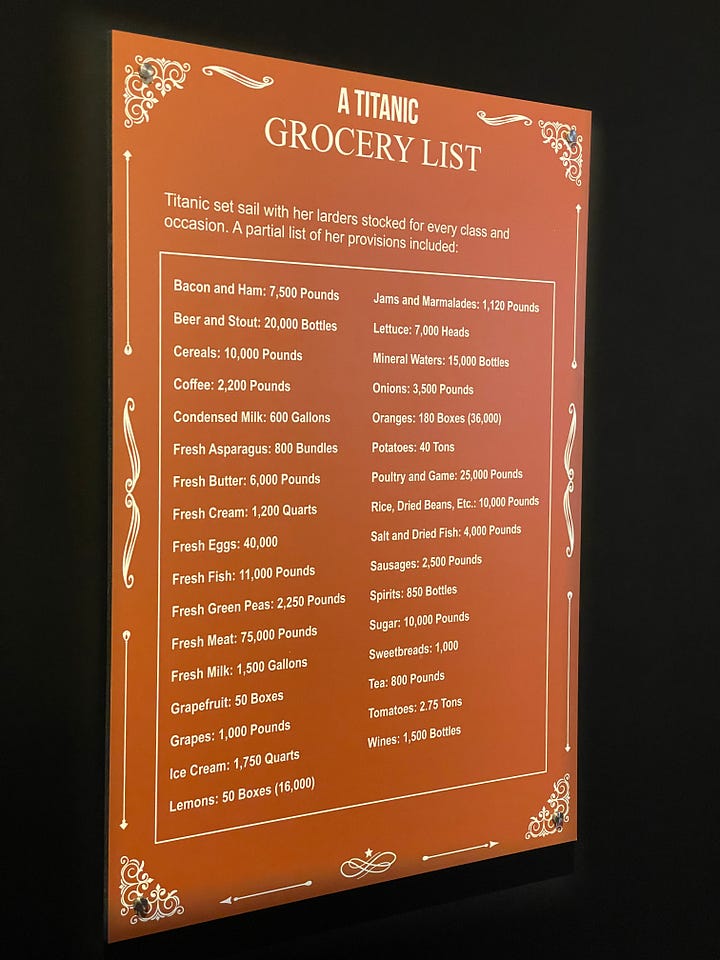

We moved through a dim warren of hallways lined with placards and portholes showing moments frozen in time. The path opened into rooms filled with artifacts: a shipbuilder’s tools, chinaware from the kitchen, a tile from the pool deck—pieces that made the story tactile.

Around the corner, dramatic recreations of the First Class Dining Salon and the Grand Staircase led toward a 360-degree projection space—the signature flourish of Exhibition Hub and Fever, the team behind this exhibit as well as Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience, which touched down in Schenectady in 2022. We moved slowly through each room, doubling back at times as details revealed themselves the way those old Magic Eye images did in the ’90s—quietly, then all at once. And in those brief moments, with the lights low and the corridors narrowing, it wasn’t hard to imagine being on the ship itself. At which point, the weight of the exhibit settled in.

Touchscreen kiosks allowed visitors to search their assigned passenger, to learn who they were and what became of them. My wife’s passenger survived. Mine did not. That contrast lingered. It sharpened conversations about class, about the decisions made, and about the individuals whose names we hadn’t known an hour earlier. We felt the loss of someone who lived and died more than a century ago.

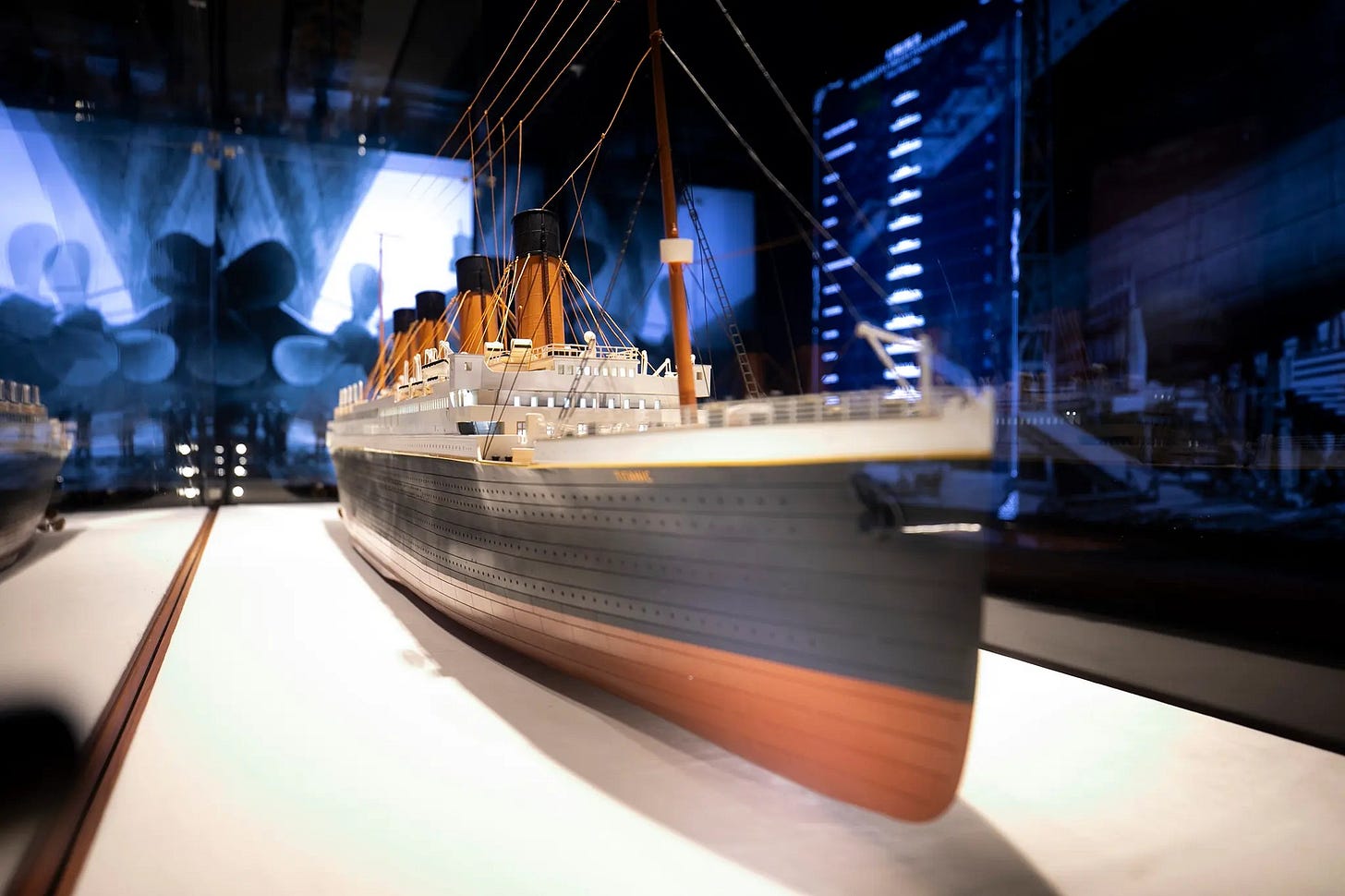

What stayed with me were the smaller details: the model of Titanic under glass, an American flag on her forward mast—a courtesy for a British ship bound for New York. The sweeping signature of J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the shipping company that owned the Titanic, on a letter—bold and unapologetic. The brief nod to the 2023 OceanGate submersible tragedy, reminding us how the ship’s pull endures. And the orchestral score threading through each room, steady and solemn, as if keeping time with the past.

My wife opted to skip the video presentation—her own form of self-preservation. I stayed. The scene echoed a familiar moment from Cameron’s film: the vantage point rising high above the ship, revealing a vast, indifferent Atlantic as Marconi messages tapped into the night. A marvel of human ingenuity, once believed to be nature-proof, appeared small—limping and alone against the open sea.

A replica of a lifeboat sat in the middle of the room. It was full. The rest of us stood or sat on the floor. I found myself wishing I could experience it all from the lifeboat.

—Michael